Things have been quiet on the blog recently, as not only have I been writing new songs as part of Fifty/Ninety (with eleven songs written and recorded so far), but also I have been finding myself a new job. My first day at work is tomorrow, and I'm really excited.

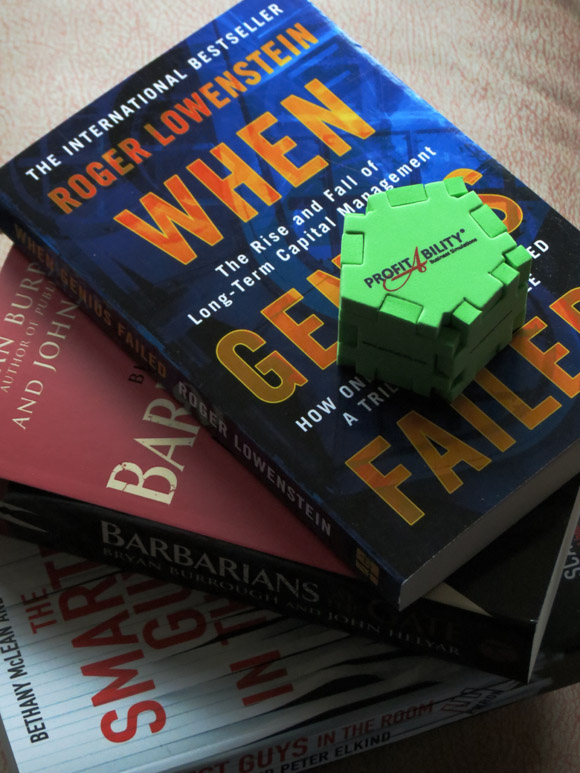

I'll still be working on instructional design and learning, but in an entirely new field for me. My current stack of reading material should give you an idea of what I'll be doing.

This means I'll be getting out and about more, and I'll be devoting much of my time to earning a salary once again. That's a good thing, but it means, I suspect, that there might not be as many new songs, social media posts, or blog updates. You'll manage, right?

The writer William Gibson has been tweeting about his trip to this year's San Diego Comic Con (and enjoying the experience, by the looks of things). As his latest venture Archangel is a comic, I thought that would be why he was attending (his first time as a panellist, as far as I'm aware). But Bill had a surprise for us. Yesterday he announced that Archangel is being adapted for television.

Yes, you read that right. A genuine William Gibson TV series will soon be crackling through the ether to a screen near you. And that's really exciting news.

There's an article on Yackler getting a lot of traction on Facebook this morning. I won't spoil the fun, but it's worth a read. Go do it now - I'll wait.

Back? Great. And you read the whole thing, right? You wouldn't want me seeing red because you skipped bits.

It has to be said that I'm the sort of person for whom the "tl;dr" comment ("too long; didn't read") is anathema. Not only do I end up reading the whole article, I frequently disappear down the rabbit hole of related content. One of the reasons my house is full of books is that I like finding out about stuff. That, after all, is why I've worked in the training industry for over 30 years. If someone quotes from a book and the writing takes my fancy, I'll buy the book and read it. It's resulted in an eclectic mix of publications inhabiting my bookshelves. If I had free access to academic papers I have no doubt I'd be doing the same thing with them. I like going into the details. I like finding out about the wider picture (oddly enough, it is possible to do both, and at the same time.)

What I don't like is when people trot out something they misheard or misread. I hate it when folks repeat statements that, if they stopped to think about them, would be laughed at and ignored. I've used the pages of this blog more than once to grumble about this sort of behaviour when I encounter it in the training industry, whether it's the oversimplification of the seven, plus or minus two model of short-term memory or trotting out the just-plain-wrong only 7 percent of what we understand depends on the words chestnut.

If a statement confirms a person's world view, they are likely to repeat it. They're not likely to check whether or not it's accurate. As the Yackler article observes, they are likely to share the statement on social media, spreading it far and wide. Critical thinking and fact checking aren't part of this process at all. And, crucially, when they do enter into play, people don't like being corrected. As Nyhan and Reifler go on to explain in the paper in that link, "Once a piece of information is encoded in memory, it can be very difficult to eliminate its effects on subsequent attitudes and beliefs."

The paper also notes a very important couple of things.

"Attempts to correct false claims can backfire via two related mechanisms. First, repeating a false claim with a negation (e.g., “John is not a criminal”) leads people to more easily remember the core of the sentence (“John is a criminal”). Second, people may use the familiarity of a claim as a heuristic for its accuracy. If the correction makes a claim seem more familiar, the claim may be more likely to be seen as true."

Repeat a lie often enough, and people will believe it.

We're back to Brexit again, aren't we?

This week I found myself wondering whether the increasing stresses of modern life might be having an effect on the tempo of the music we listen to. Our hearts beat faster under stress - might that mean that the music we like beats faster, too?

The Internet being what it is, it should come as no surprise to discover that someone has been tracking that data - up to 2013, at least. And I was very surprised to discover that the average beats-per-minute count of popular songs has stayed pretty constant over the last few decades. The fastest era for pop so far was back in the 80s, the fastest year recorded being 1980 when the average tempo of songs topped out at 109.567 bpm.

That got me wondering whether bpm preference might be dependent on something neurological rather than physiological, and sure enough, there are some truly fascinating papers out there suggesting a link between rhythmic stimulation of the motor cortex and the auditory system. There is an intimate connection between beat perception and motor functions of the brain. Indeed, studies of rhythmic walking to music suggest a preference for tempos of between 110 to 120 bpm. Aha! Reading still further, things get even more interesting. At present, our rhythmic ability is thought to be linked to the vocal learning process, which humans share with some large mammals and several species of birds; Lots of other animals can keep the beat as well as (or, in the case of some of my non-musical friends, significantly better than) humans. Rhythmic appreciation of music is not a uniquely human trait; what a lovely and deeply profound discovery to make.

In view of the other post I made today it should come as no surprise that I'm now wishing I could afford to buy a copy of Justin London's Hearing In Time: Psychological Aspects of Musical Meter because it sounds fascinating. But asking twenty five quid for the Kindle version is, quite frankly, ludicrous.

My investigations left me feeling very sorry for rhesus monkeys, though. When it comes to keeping the beat, they just haven't got what it takes.

The Bolshoi Ballet, headquartered in Moscow, is widely regarded as one of the foremost (and oldest) ballet companies in the world. It gets its name from the Bolshoi Theatre, where it was founded. But the romance of the name loses a little in translation; it means "the large theatre" so in English, the company would be called the Big Ballet Company.

"Bolshoi" is also the root of the word Bolshevik, the "Majority Party" founded by Vladimir Lenin and Alexander Bogdanov in 1898. When it was formed, it was anything but the majority - at least on a consistent basis. Under Lenin, the Bolsheviks started calling the other faction of the party the Minshevik, or "Minority Party." It still amazes me that Lenin's opponents just rolled over and accepted the derogatory name he gave them; it's a dick move of the highest order. Names have a tendency to be self-fulfilling, because many people will believe things if they're presented with sufficient conviction, even if petty things like truth are conspicuously absent; in this case, you know how the story ends up. Where the Minsheviks were more in favour of considered debate and gradual reform, the Bolsheviks favoured violence and revolution. After October 1917 the Minsheviks really were the minority party. They had less than 4% of the vote to the Bolsheviks' 25% and the Socialist Revolutioinaries' 57%. Democracy be damned; the Bolsheviks had the Red Army behind them, so one civil war later, Lenin was in control and the rest is, as they say, is history. Just shy of a hundred years later, the destinies of entire countries are still being shaped by what people are saying is the truth rather than by what actually is the truth. And once again, this behaviour is accepted by people who really ought to know better. Forget fact-checking, who wants to do that?

The reason I mention all this is because I recently read Robert McCrum's piece in The Guardian picking Thomas Kuhn's The Structure of Scientific Revolutions as one of the "100 best nonfiction books of all time." I nearly spat my coffee over my keyboard when I read the headline, and the description that Kuhn is "still widely accepted" nearly caused another accident. At the risk of covering some old ground, I want to explain why this is - excuse me - bullshit. The Guardian is trolling its readers, even though most of them won't realise it. I've read Kuhn - I still have a copy of the book upstairs which I bought when lecturer after lecturer referred to him during my Masters Course. In the book, Kuhn presents science as, in essence, a debating competition; the way things are depends upon who has the most eloquent and convincing explanation of how the Universe works. Kuhn refers to these explanations as paradigms, and when preference shifts from an old paradigm to a new one, we get a paradigm shift (yes, the book is where the expression was coined).

But the language with which Kuhn then attempts to justify his assertion is so deliberately opaque and vague that it takes a considerable amount of effort before you realise that he's failed to make his case. He's almost wilfully inconsistent: in Criticism and the Growth of Knowledge Margaret Masterman counted 21 different ways in which he uses the word "paradigm". Kuhn denied this, although in the same book he admits that his presentation of the concept was "badly confused."

The idea that new scientific theories are accepted because they are able to make a larger number of more accurate, and more detailed predictions about future events than established theories do is absent from Kuhn's work, at least explicitly. In his obtuse way, Kuhn might argue that this is what he is referring to when he talks about "applying the paradigm," which is a great example of Kuhn saying something so vague that it can be retrospectively claimed to mean absolutely anything at all. Elsewhere in the book, though, Kuhn writes at length about science as "puzzle solving," portraying it as an activity no more taxing than completing a crossword. That is most emphatically not the same approach.

The great physicist Freeman Dyson demolished Kuhn's argument in a single paragraph in his book Imagined Worlds, on pages 49 and 50 (the emphasis is mine):

"There are two kinds of scientific revolutions, those driven by new tools and those driven by new concepts. Thomas Kuhn in his famous book, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, talked almost exclusively about concepts and hardly at all about tools. His idea of a scientific revolution is based on a single example, the revolution in theoretical physics that occurred in the 1920s with the advent of quantum mechanics. This was a prime example of a concept-driven revolution. Kuhn’s book was so brilliantly written that it became an instant classic. It misled a whole generation of students and historians of science into believing that all scientific revolutions are concept-driven. The concept-driven revolutions are the ones that attract the most attention and have the greatest impact on the public awareness of science, but in fact they are comparatively rare. In the last 500 years, in addition to the quantum-mechanical revolution that Kuhn took as his model, we have had six major concept-driven revolutions, associated with the names of Copernicus, Newton, Darwin, Maxwell, Freud, and Einstein. During the same period there have been about twenty tool-driven revolutions, not so impressive to the general public but of equal importance to the progress of science. Two prime examples of tool-driven revolutions are the Galilean revolution resulting from the use of the telescope in astronomy, and the Crick-Watson revolution resulting from the use of X-ray diffraction to determine the structure of big molecules in biology. The effect of a concept-driven revolution is to explain old things in new ways."

Kuhn seemed to abandon the ideas presented in Structures with a considerable amount of alacrity. In a lecture recorded in his book The Sun, The Genome, and The Internet: Tools of Scientific Revolutions Dyson recalls that he met Kuhn (in 1962) and confronted him about the book. Kuhn didn't take it well:

"A few years ago I happened to meet Kuhn at a scientific meeting and complained to him about the nonsense that had been attached to his name. He reacted angrily. In a voice loud enough to be heard by everyone in the hall, he shouted, "One thing you have to understand. I am not a Kuhnian.""

At least Kuhn didn't try to throw an ashtray at him.

The Guardian's assertion that Kuhn is still "widely accepted" isn't a fair representation of current science, judging by some of the essays that I've read. Yet the idea that the nature of reality depends upon what we say it is is more popular than ever, at least amongst people without a scientific background. That may be one reason why we've ended up in the current era of post-truth politics. And that's working so well for us at the moment...

Tomorrow is July the 4th, which heralds the beginning of this year's Fifty/Ninety activities, in which I will attempt to write fifty songs in the ninety days up to the first of October. I can't really give a better explanation of why I do this than the one I gave exactly a year ago. But this year I want to think a little bit about how Fifty/Ninety makes us better songwriters.

The numbers have changed quite a bit since I wrote last year's blog post; the total count of compositions I've written or co-written since I started taking part now stands at somewhere around the 340 mark. And believe me, it's all about the numbers. Fifty/Ninety, like its close relative FAWM is an invaluable learning experience for songwriters, because it gets you writing songs. Sitting down and actually writing songs for other people to listen to is a great way of learning how to write songs. That sounds obvious, right? It isn't as clear-cut as that in real life, though.

A lot of people who harbour an ambition to be a songwriter (by which I mean me, some thirty-odd years ago) have an idea that songwriting is a hallowed, spiritual event that only takes place on special occasions at particular moments, that it has to take place when conditions are just right, and that it never happens - should never happen - otherwise. The writing process is often viewed by non-writerly people as involving stuff like bursts of inspiration, or being seized by the creative muse and suddenly hearing a song, complete, in your head and scrambling to write it down. As a result of this unrealistic image, the novice songwriter sits around waiting for these mythical things to show up before trying to actually write anything. That means they either never write anything at all, or they write so little that they don't see an improvement over time. That leads to disillusionment, and it also perpetuates their view that the ability to put a half-decent song together is some sort of superpower.

It really isn't.

Like many other things, songwriting is work. It takes effort. And the secret to getting good at it is that you have to put the hours in, regardless of your motivation level.

During Fifty/Ninety and FAWM, the whole focus is on writing even when you don't feel inspired or motivated. Not feeling like the muse is on your side today? Tough. Write a song anyway. Write another one tomorrow. And another one the day after that. Not for nothing does the FAWM website feature a quote from Jack London about not loafing around waiting for inspiration but rather "light out after it with a club." It's the act of writing that's important.

Fifty/Ninety and FAWM embody the principle of learning by doing. I've worked in the training and education field for a long time and over and over again, I've seen the approach yield positive results in many different industries, for many different skill sets, physical activities, and areas of knowledge. Yes, knowing the theory behind a subject is hugely important. So is the experience of watching or listening to someone else demonstrate their expertise. But actually doing something is very different to watching a video or reading an article about how someone else does the same thing. And the more you actually do something, the more likely it is that you will become good at it. While the "10,000 hour rule" for achieving mastery of a subject that was popularised by Malcolm Gladwell has been refuted by the scientist who researched the subject in the first place (and by subsequent studies), deliberate practice is still an essential part of the learning process. But as I wrote in my blog last month, there are particular ways of practising that are helpful, and others that are less so.

I used to work with a specialist, or Subject Matter Expert (SME) who had been working in a particular field for thirty years. The trouble was, his advice often contradicted the information I was being given by his colleagues, many of whom were considerably younger. When I investigated further, his advice often turned out to be wrong. Eventually someone who worked with him summed up what was happening:

"He might tell you he has thirty years' experience, but in reality he's just repeated that first year of experience thirty times. He never learned from it."

I'm sure you've met people like that, too. The SME's ego was in control, and he wasn't interested in improving or learning any more because in his opinion, he didn't need to: he already knew best. This phenomenon has been researched extensively in psychology, where it's known as the Dunning-Kruger Effect. Getting past this state is important, because we then realise just how much more we need to know and can start doing something about improving ourselves.

A big part of achieving that depends on help from other people. In terms of the pedagogy behind it all, a very helpful concept is that of communities of practice, based on research by Jean Lave and Etienne Wenger. People take part in a "shared human endeavour" and as they do so, they interact with each other and learn how to do it better. That's exactly the concept behind Fifty/Ninety and FAWM. They are hugely powerful learning tools for people who write, record or perform songs.

I know that a lot of the folks doing Fifty/Ninety and FAWM have many different reasons for taking part and many are totally happy with the level of skill that they've already achieved. That's totally OK. Not everyone wants detailed feedback about their work. Our egos can sometimes push back against being told how we could do a thing better. I understand that. Participants are a nice bunch of folks, and they play nice. Sometimes simple feedback like "You're doing great!" is all we think we need. But while it gives the writer a nice fuzzy feeling, it does them a disservice, because they can't learn anything from it. When I comment on a song, my intent is always to encourage the writer to improve, because that's what I hope to get from people commenting on my work. And I pay a lot of attention to that sort of commenting, because I know how important it is. In the years I've done both Fifty/Ninety and FAWM, it's been the constructive, detailed feedback I've been given that has stayed with me. It's been the suggestions for doing things differently that have resulted in sudden, remarkable improvements in the results I get. This year, as ever, I'll be asking for detailed feedback on everything I write. I might not agree with all of it, and of course I reserve the right to ignore any advice I'm given, but I know that it will be of huge benefit to my writing process.

Would that all other human endeavours could be approached with the same helpful, constructive attitude.